Unlikely Monuments

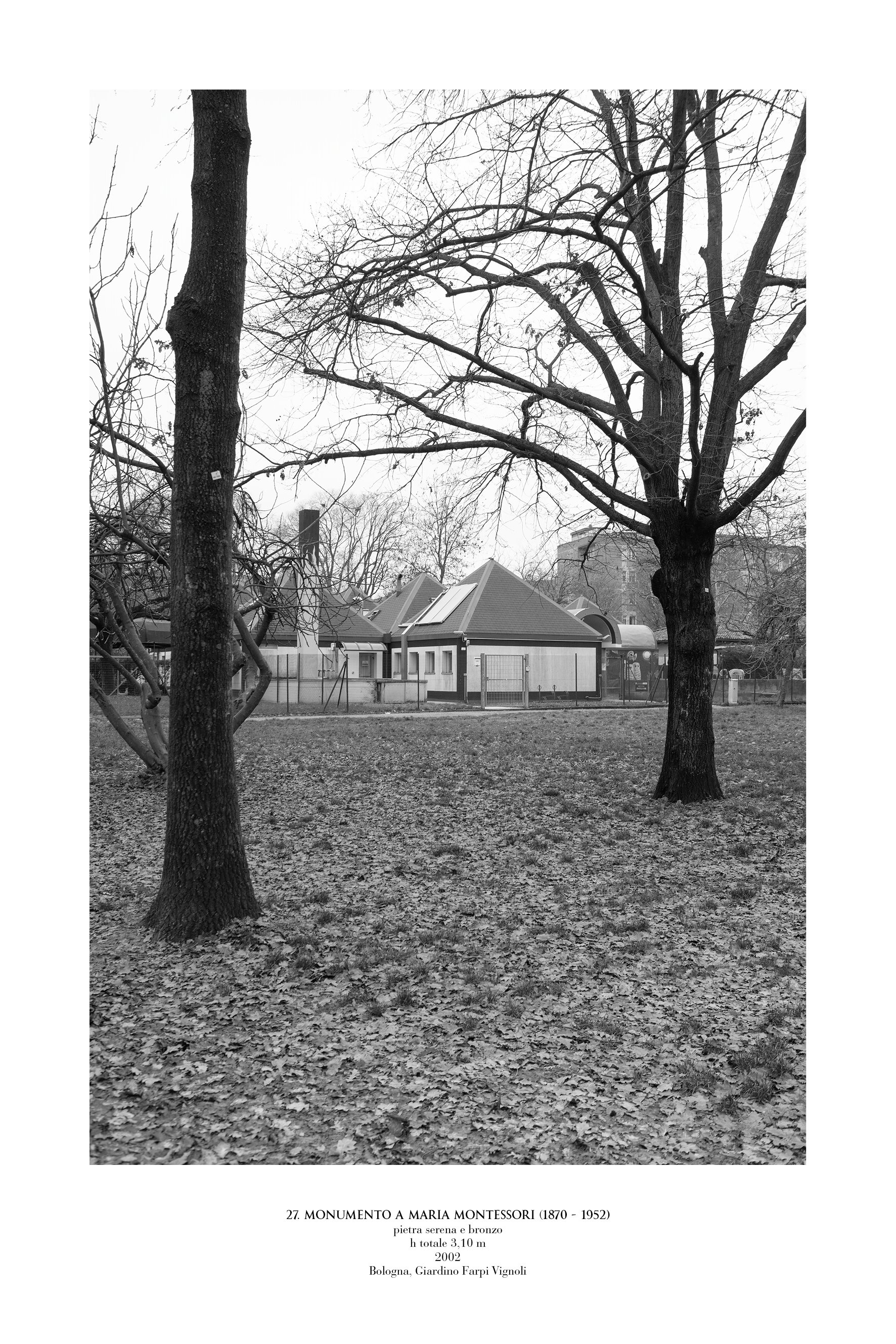

History and memory are, in different ways, a construction, like photography, and do not represent or tell what immediately appears but rather what we want to preserve, reveal, or reflect on. Monuments dedicated to women who played a public role or gained a noteworthy position in the public sphere, be they known, unknown, or forgotten, are undoubtedly unlikely, as are the spaces where they are placed. What is proposed is a reflection on the meaning of "monument", on how we are remembered and how we would like to be represented, perhaps through other forms than the patriarchal ones monuments have taken on.

Unlikely Monuments is developing in many ways, to suggest a reflection on public memory, inclusions and exclusions in history and urban space, through photography.

Unlikely monuments. Excerpt from the catalogue is the ongoing series of unlikely monuments in the city of Bologna. Monumenti improbabili / Unlikely monuments. Public Art Commissions are commissions taking place in communities and townships that would like to participate in selecting a woman and a space to collocate an unlikely monument, Unlikely Monuments. In Dialogue is a process that activates a dialogue between unlikely monuments from the Excerpt from the catalogue series and places, sparking reflection through symbolic comparisons.

Unlikely Monuments

Excerpt from the Catalogue

The catalogue is presented as an excerpt and the series is ongoing. Even the gaps and the cataloguing itself may be filled or continued through proposals, making this cataloguing process collaborative. People are indeed encouraged to find other connections with the places. All these monuments are imagined in Bologna, Italy, the regional capital of Emilia-Romagna.

Forty images were first shown at Istituto Storico Parri of Bologna, in an exhibition promoted by Istituto Storico Parri and Lavì City, curated by Giovanna Calvenzi on the occasion of Art City Bologna 2024. The project has the patronage of the Municipality of Bologna.

12. Dorothea Lange, 13. Margherita Hack, 15. Maria Callas, 17. Simone De Beauvoir, 21.Irma Bandiera, 23. Anita Garibaldi, 27. Maria Montessori, 31. Aleksandra Kollontaj, 32. Francesca Morvillo, 34. Frances Thompson, 43. Hannah Arendt, 45. Billie Holiday, 51. Nilde Iotti, 53. Alda Merini, 54. Sibilla Aleramo, 63. Virginia Oldoini Veraris Contessa di Castiglione, 73. Joice Lussu, 81. Olga Prati, Maria Chindamo, 85. Laura Bassi, 91. Ersilia Caetani Lovatelli, 95. Virginia Woolf, 97. Rosa Parks, 101. Ruth Bader Ginzburg, 103. Rosa Luxemburg, 105. Rukhmabai, 107. Anna Kuliscioff, 109. Simone Weil, 112. Mabel Hampton, 114. Mathilde Fibiger, 116. Maria Sybilla Merian, 117. Alfonsina Strada, 119. Tina Anselmi, 122. Rosa Genoni, 125. Mary Beatty, 127. Olympe De Gouges, 130. Jane Austen, 132. Teresa Noce, 115. Lavinia Fontana, 138. Anna Atkins, 141. Frances Benjamin Johnston, 144. Maria Ilva Biolcati, Milva, 147. Emma Goldman, 151. Ursula Hirschmann, 153. Florence Nightingale, 155. Alba de Cespedes, 158. Wangari Muta Maathai, 160. Marie Curie, 162. Eleanor Roosevelt, 164. Rita Levi Montalcini, 166. Emily Dickinson, 169. Lee Miller, 173. Eileen Gray, 177. Emmeline Pankhurst, 179. Properzia de Rossi, 182. Goliarda Sapienza, 184. Sojourner Truth, 186. Carla Accardi, 189. Daphne Caruana Galizia, 192. Anna Politkovskaja, 204. Agatha Barbara

Archival fine art prints 40 x 60 cm (2020-2025) - Edition of 5 + 2 AP

Unlikely Monuments. Excerpt from the Catalogue.

Limited edition of 20 artist’s books containing 50 digital prints (from 12 to 164) and a hand-sewn pamphlet, 30 x 45 cm in a 32 x 47 x 3 cm plexiglass case.

Texts, photographs and design © Sonia Lenzi, Typography and layout © Sara Murrone, essays by © Giovanna Calvenzi, © Lucy R. Lippard and © Uliana Zanetti

Tosca Press, 2024

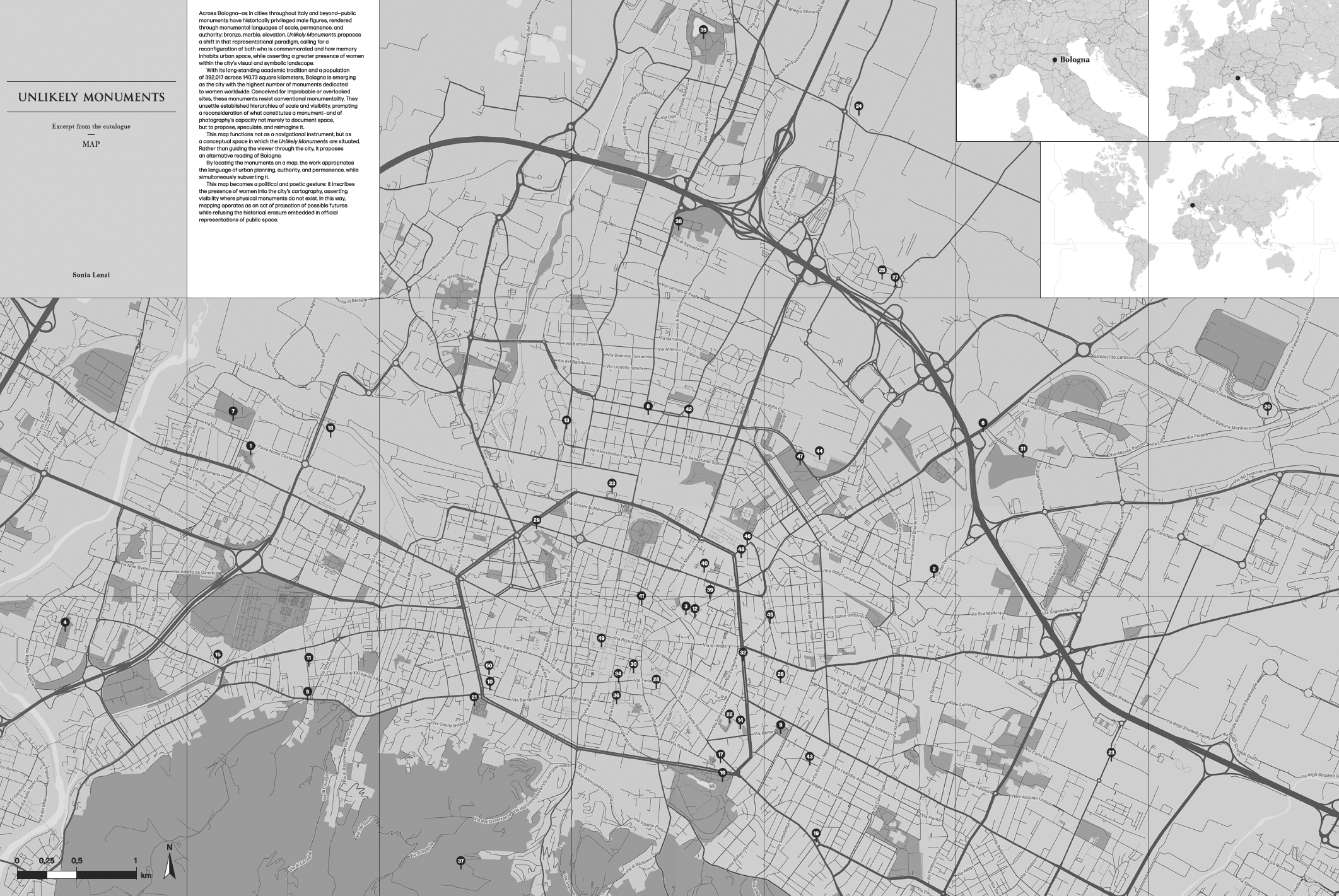

Unlikely Monuments. Excerpt from the catalogue. Map.

A map with the 50 unlikely monuments included in the artist’s book. The map functions not as a navigational instrument, but as a conceptual space in which the unlikely monuments of this series are situated. Rather than guiding the viewer through the city, it proposes an alternative reading of Bologna. By locating the monuments on a map, the work appropriates the language of urban planning, authority, and permanence, while simultaneously subverting it.

Open: 90x60 cm

Folded: 20 x12,85 cm

Printrun: 250

ISBN: 979-12-243-1792-0

Concept, photographs and texts: © Sonia Lenzi

Typography and layout: Sara Murrone

Tosca Press, 2026

Unlikely Monuments

Monumenti improbabili / Unlikely Monuments. Public Art Commissions

A Public art project started in October 2025, which is currently taking place in three Municipalities of the Metropolitan city of Bologna. The citizens are invited to form a Public Art Commission to identify women and places where monuments should be symbolically placed, thereby forming, in the process, a collective memory of their own community. The project has been awarded a grant from the Fondazione del Monte di Bologna e di Ravenna.

Unlikely Monuments

In Dialogue

Starting from the ongoing series "Unlikely Monuments. Excerpt from the catalogue", a dialogue is created between the places, the unlikely monuments, the women represented and the viewer. This process activates a mechanism for individual and collective imagination and memory, starting with these subjects — the urban spaces, the unlikely monument— to rethink the modes of inclusion and exclusion from history and the related social differences and inequalities.

The first "In Dialogue" is presented at Casa Carducci, in Bologna. Symbolically opposite to the house, there is the unlikely monument to Alda Merini, not far from Leonardo Bistolfi's monument to Giosuè Carducci. Merini and Carducci: two antithetical personalities and poets, who lived in different eras, confront opposing ideas of the representation of public memory in the austere spaces of the last home of the poet of unified Italy.